“For me, the ‘Weimar Bach,’ that is to say, his early period, was always one of the greatest mysteries and miracles of musical history” Nikolaus Harnoncourt, founding patron of the BACH BIENNALE WEIMAR, 1929–2016)

This statement captures the core of Bach’s years in Weimar. For by the age of twenty-three, the young Bach was already composing with such perfection that it is often impossible to date his Weimar works. They are indistinguishable from those that came later—namely, consummate music!

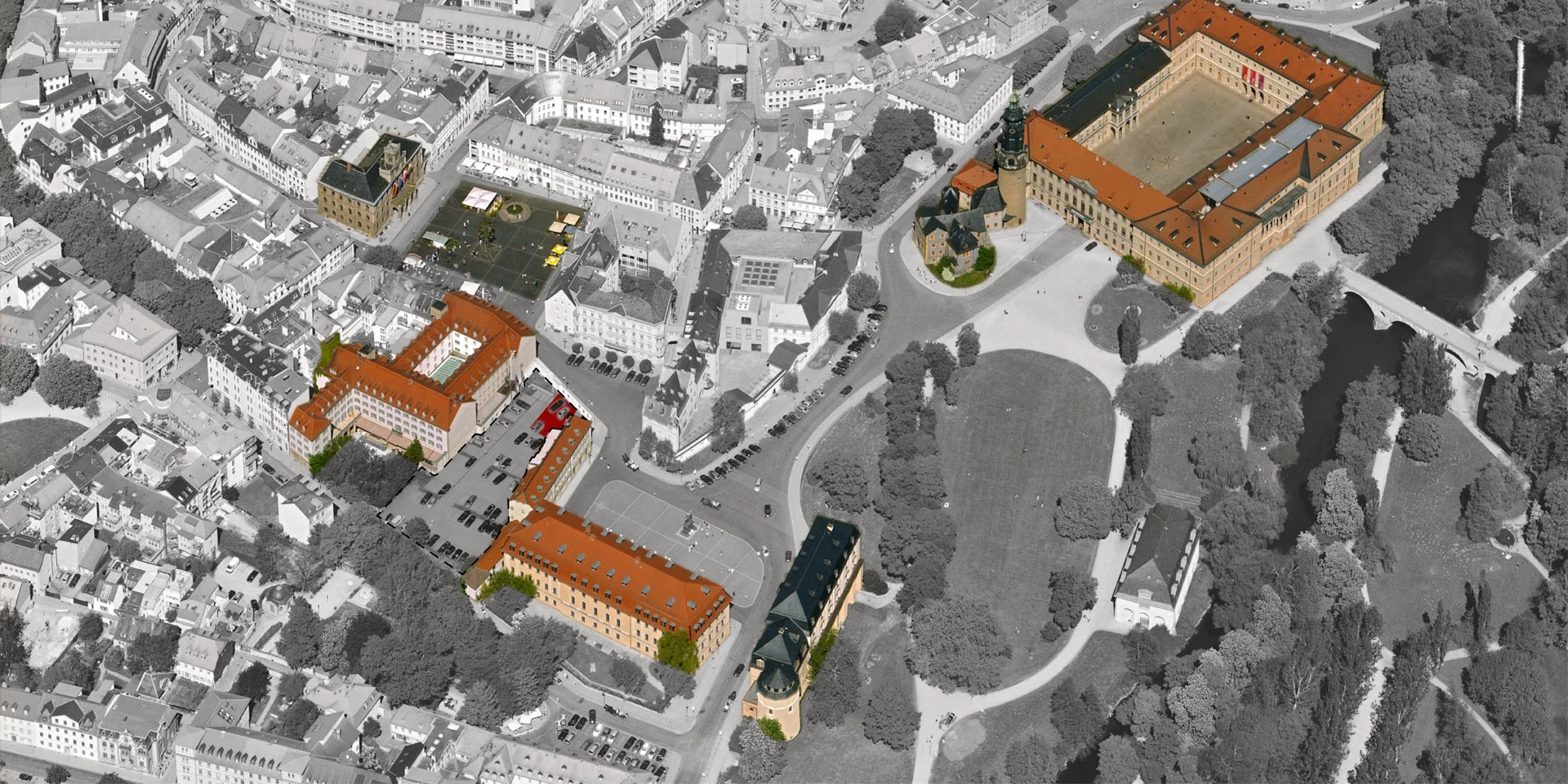

The Weimar years had a profound impact on Bach: It was here that Bach became himself and found his unique and unmistakable voice. Until the end of his life, he was to build upon that which he created here.

Where are the reasons to be sought for this extraordinary creative phase? It is certain that Bach became acquainted with and studied a large amount of Italian music in Weimar –

works by Vivaldi, Corelli, Legrenzi, Pergolesi, and others. Bach absorbed this music and from then on “spoke,” that is to say, composed perfectly in Italian.

His immense and exuberant talent also sought out enough freedom to experiment in all directions. His Weimar years and the works he composed there are like the eruption of a “musical fountainhead” of elemental, unbridled abundance. In terms of excessive instrumental virtuosity, experimental combinations of instrumental, shocking modernity, and utmost abstraction, this “young savage,” the Weimar Bach, is unrivaled!

In Weimar, a large part of the “universe” of his organ works came into being, over thirty-five vivid, multifaceted, and beautiful cantatas, numerous harpsichord solo works that are unparalleled in their boldness, several concerti from the singular “cosmos” of the Brandenburg Concertos, as well as parts of his epoch-making solo partitas for violin, and at least the first part of the Well-Tempered Clavier; the latter two are still a kind of “grammar” for violin and keyboard instruments, unrivaled in both crystalline architecture as well as emotional profundity.

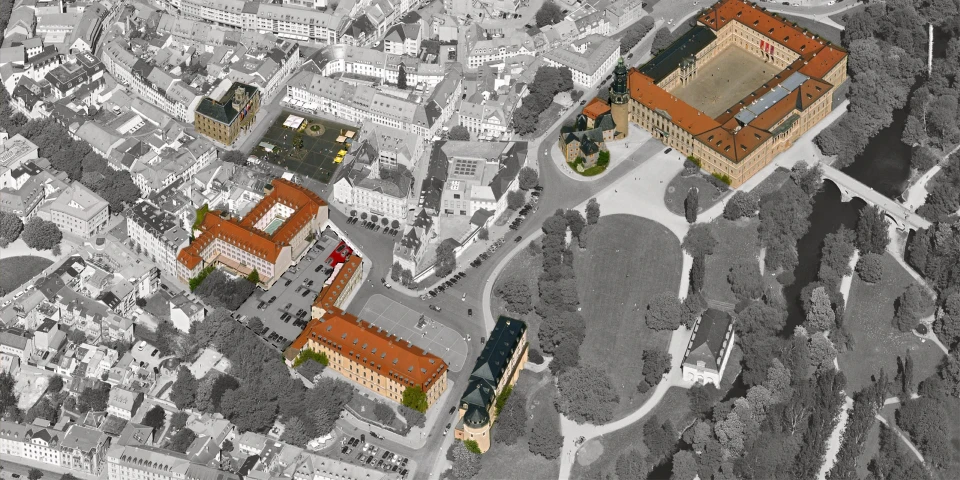

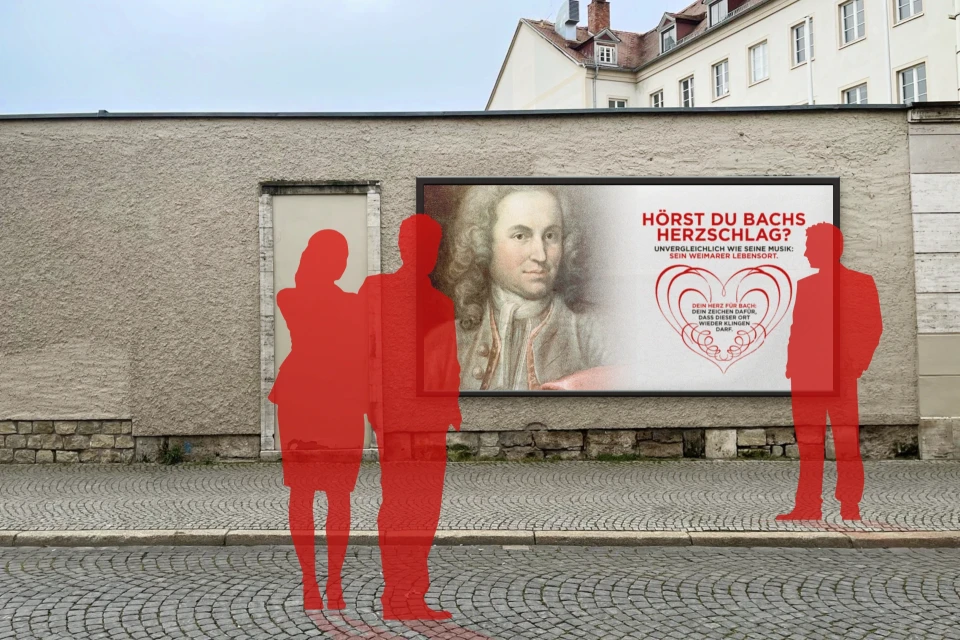

When Bach left Weimar, he was only a little younger than Mozart when he died. Weimar is therefore a Bach city to the same extent that Salzburg and Vienna are Mozart cities. In contrast to Salzburg or Vienna, Weimar does not yet bear this rank with the same naturalness – and not with the same pride. There is still room for improvement here ...

It is now time to recognize and show Bach’s Weimar years for what they are: A creative eruption – powerful, free, unorthodox, and unsurpassed to the present day.

Not even by Bach himself.